Life and Death

- JanetJoanouWeiner

- Mar 13, 2021

- 3 min read

Our little town of St. Hippolyte du Fort boasts not one but two old-fashioned cemeteries. There's a reason for this: one was for Catholics, the other for Protestants.

The Wars of Religion here, over two different centuries, have left their mark on the land and in people's hearts.

Cimitière Catholique

Cimitière Protestante

The first round of these conflicts dates back to the 16th century, with clashes between the Catholic monarchy and powerful Protestant (Huguenot) nobles. Catherine de Medici, the Catholic Queen Mother initially tolerant towards the Huguenots, later hardened her stance.

Catherine most likely instigated the infamous St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. Thousands of Huguenots gathered in Paris for her daughter's wedding to Protestant Henri of Navarre. Horrific violence spread throughout France in the following weeks. Estimates of the death toll run between 5000 to 30,000, the majority of whom were Protestant.

St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, Paris, 1572, Painting by François Dubois

Catherine de Medeci after St. Bartholomew's Day massacre Painting-By Édouard Debat-Ponsan

After this bloody nightmare, Henri converted to Catholicism, famously stating: "Paris is worth a mass." Once crowned King Henri IV, he issued the Edict of Nantes, guaranteeing Huguenots' rights and freedoms. Although still treated with hostility, Protestants could live, worship, and prosper without restraint for the next 100 years.

Then came the reign of Louis XIV, the "Sun King" who disdained sharing his light with another. Throughout the early 1680s, he slowly chipped away at Huguenot rights–limiting their access to certain professions, limiting when, where and how many could meet together (eek- that sounds too familiar).

Eventually, the king deployed dragoons, ferocious mounted soldiers to sweep through Protestant regions. With implied permission to abuse the inhabitants, the troops lodged in Protestant households steal their possessions–anything to force them to convert.

Finally, he revoked Henri's Edict of Nantes. With the stroke of a pen, he outlawed Protestantism. Persecution to force conversions increased massively, and up to 200,000 Huguenots fled France. Their arrival in England, Switzerland, Canada, United States, and South Africa brought great blessings with their knowledge and work ethic.

Another century of religious civil war in France finally ended with the French Revolution. Protestants were then guaranteed the right to meet, educate their children, and exercise their profession freely…to exist.

For the most part, these conflicts between Catholics and Protestants are a thing of the past. When I teach young French people in one of our training schools around the country, they often have very little awareness of this period of history. But like all history, it is a part of the national story and has impacted the country.

The earliest tombstone death dates in the cemeteries here are from the mid-1800s. Protestantism was granted legitimacy in 1789, so apparently, it took a while to establish the Huguenot cemetery. During the wars of religion, Protestants were not allowed to marry, baptize, and buried family members on their land, marked with a Cypress tree.

I doubt I'm the only one who finds these cemeteries interesting. The older, the better, in my opinion. Names and dates engraved onto various types of stone is–dare I say it?–charming. That might not be an appropriate word for tombstones, but I can't help but delight in the old-fashioned fonts, dates, and of course, the names. Alphonse, Philippine, Albertine, Marcelline, and the most surprising: the lovely...Zulma!

Wrought-iron design work surrounds or ornaments the most ancient graves. These are my favorite, even if they evoke a particular poignancy. They look a bit tilted and forlorn yet represent another era; real people and stories lived.

There's also a certain sadness in cemeteries, especially when dates reveal that the span of someone's life was short. My heart always goes out to the parents who have lost a young child. There are also many plaques honoring those who gave their lives in service of their country, most at very young ages.

Many tombs hold family members spanning generations. Apparently, wealthier Catholics and Protestants built little houses (I suppose they're called mausoleums, but that word sounds so morbid to me!) Either way, it speaks to me of the bonds of family-across life and death.

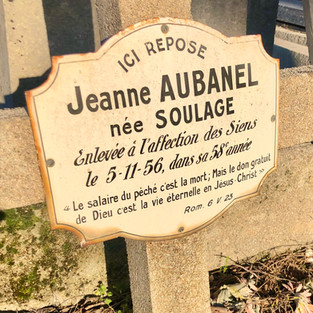

I think how we see cemeteries depends on perspective—death unto death…or…death unto life. While crucifixes adorn many tombs in the Catholic cemetery and Huguenot crosses in the Protestant one, both speak of faith in life beyond this one. Bible verses are etched onto many of the Protestant tombstones:

Love one another as I love you...

The Lord is my light and my deliverance...

As my father loved me, I love you, dwell in my love...

I give you my peace...

The wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life in Jesus Christ...

Watch because you don't know the day nor the hour...

Life is beautiful, despite its difficulties. Through the massive love of Jesus, we live in hope now and for ever.

Oui, la vie est belle…

LIFE is beautiful…

Thank you, Janet for the wonderful trip through history and a eye opening walk through cemeteries. I love your comment, that no matter one’s stance on religious identity, their is a driving force to grasp faith and believe their is a God who gives hope. I think of this often when visiting Catholic Churches in Italy. Their intricate and extensive work shows a longing to bring beauty in a place to worship God.

Death to Life!

P. S. How can I get a copy of your book?